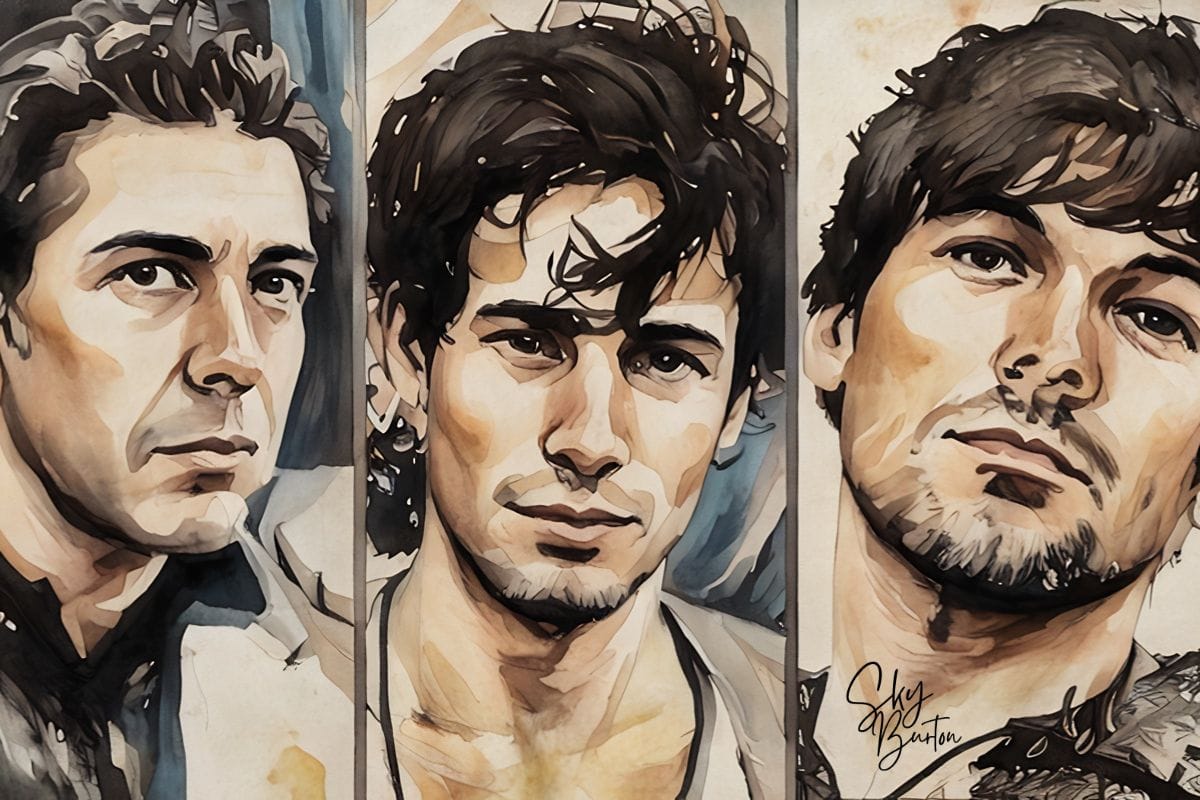

How Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and Louis Tomlinson Speak the Same Language

What binds Cohen, Buckley, and Tomlinson is not genre or fame. It’s something quieter and more sacred. They stood apart, each in their own time, each in their own way. And in doing so, they created work that doesn’t just last, it lives.

Some artists write hits. Others write hymns for the human experience.

Leonard Cohen. Jeff Buckley. Louis Tomlinson.

Three men, three distinct eras, and three wildly different public images, yet somehow, they form a lineage. Not by industry standard or playlist algorithm, or even vocal strength but by emotional resonance. Listen beyond the noise, the headlines, the myths and you’ll hear it: the subtle language of truth, grief, defiance, and spiritual ache.

They are poets of a different kind. The kind that doesn’t clamor for attention but holds it—gently, honestly, and with a kind of haunted clarity that lingers long after the music ends. They didn't need to shout with flashy visuals to be heard.

They Were All Misread at First

Cohen was dismissed early on. A poet-turned-singer with a voice that critics called “monotone” and “limited,” as if range were the point. But he wasn’t trying to seduce radio. He was unraveling the sacred and the profane in equal measure. He spoke in riddles and revelations. He wasn’t here to entertain; he was here to understand.

Buckley, too, was often misunderstood. Beautiful, elusive, and difficult to label, he resisted being locked into genre or narrative. He didn’t want to be "the next Dylan" or "the next anyone." Even with his supernatural voice and model looks, Buckley had no interest in being packaged. That refusal may have limited his commercial reach, but it preserved his authenticity. His only studio album, Grace, became a posthumous masterpiece—because it wasn’t chasing trends. It was chasing truth.

Louis Tomlinson's journey is perhaps the most public and yet still the most dismissed. Branded as the "least popular" in One Direction by critics, underestimated by media, he was often written off as the guy in the background. But fans knew better. And now, so does anyone listening. In his solo work, he’s revealed himself to be the emotional backbone of the band, the one who sees the cracks and writes the light that shines through them. His songs don’t beg for fame—they stand for resilience.

They Carried Grief Like a Sacred Thing

Grief threads through each of their bodies of work—not as spectacle, but as scripture.

Leonard Cohen didn’t just write about sadness; he gave it architecture. In songs like Famous Blue Raincoat or Suzanne, there’s a quiet ache, as if he’s chronicling a heartbroken pilgrimage. Grief, to Cohen, was a teacher, a slow-burning candle held in reverence.

Jeff Buckley’s music sounds like someone mourning something they never even had. There’s a ghostliness to his voice, especially in Lover, You Should’ve Come Over or his aching, stripped-back cover of Hallelujah. (Ironically, a Cohen song passed from poet to angel, then to myth.) Buckley’s death by drowning at age 30 only deepened the weight of every note he left behind.

Louis Tomlinson’s grief is more recent and more raw. The death of his mother and sister, so close together, could have broken him. His known challenges within the music industry and behind the scenes continue today. They did everything they could to suppress his voice, identity, and natural talent. Instead, he wrote. Two of Us, Holding On to Heartache, Chicago, Saturdays. These aren’t pop songs. They’re offerings. He doesn’t wallow in pain, but he doesn’t skip past it either. He stays with it. And in doing so, he creates space for us to stay with ours.

They Didn’t Chase Fame—They Rejected It

Fame was never the goal for these men. It was the obstacle.

Cohen never catered to pop standards. He released albums when he felt moved to, often years apart, his work thick with biblical references and existential questions. His popularity surged late in life, almost against his will. He was always more interested in the work than the applause.

Buckley openly mocked the idea of superstardom. He refused to promote his singles in the traditional ways and walked out of photo shoots. He was obsessed with artistic purity, sometimes to his own detriment. He knew the machine wanted to devour him, so he stayed on the fringes, preserving the essence of his voice, both literally and spiritually.

Tomlinson, though forged in the furnace of global fame, has since taken the most unorthodox route. While some former bandmates leaned into pop spectacle, Louis built a career around vulnerability. He tours relentlessly, connects directly with fans, and writes songs, alongside his creative team, that are distinctly his. No gimmicks. He’s turned down flash for the sake of longevity. He’s not playing the industry’s game. He’s rewriting it.

They Refused to Be Pigeonholed

Genre-defiance is one of the quietest forms of rebellion.

Cohen blended folk, jazz, and liturgy. His lyrics could fit in a chapel or a dive bar. He wasn't just writing songs, he was documenting spiritual tension in modern life.

Buckley crossed genres like a river—rock, jazz, opera, soul. There are moments in Grace that sound like gospel, then slide into chaos. That fluidity kept the industry from knowing what to do with him, which made him harder to sell, but impossible to forget.

Tomlinson may have started in pop, but his solo work veers toward Britpop, indie rock, and lyrical storytelling more at home in a smoke-filled pub than a stadium. He’s not trying to be everything to everyone. He’s becoming more himself song by song, show by show. It's been a long journey coming from superstar teenager through his own evolution, all the while knowing there would be an inevitable shift in his audience.

That refusal to be pinned down is a form of creative defiance. And it’s something all three of them share.

Masculinity, Rewritten

Perhaps what’s most radical about these men is how they portray masculinity.

Cohen's masculinity was philosophical. Wounded, romantic, inquisitive. He made it okay to ask big questions, and to do it in a whisper.

Buckley was soft and intense. His masculinity was not defined by dominance, but by range—emotional, vocal, spiritual. He could cry in falsetto and make it sound like liberation.

Tomlinson’s masculinity is grounded and loyal. He doesn’t posture. He protects. In interviews, onstage, and in his writing, he chooses brotherhood and sensitivity. In an era of hyper-performance, his quiet emotional presence is revolutionary.

Together, they remind us that real strength is vulnerable. That real art doesn’t need armor.

The Echo Between Them

What binds Cohen, Buckley, and Tomlinson is not genre or fame. It’s something quieter and more sacred.

They sing to the people who sit at the edge of the crowd, unsure of their place in the world. They offer a language to those who have lost, questioned, grieved, endured.

They stood apart, each in their own time, each in their own way. And in doing so, they created work that doesn’t just last, it lives.

So next time you hear Louis sing Chicago, or stumble across a dusty copy of Grace, or hear Cohen’s Anthem echo through an solemn room—listen a little deeper.

These men aren’t just singers.

They’re companions.

For the ones who still believe in the power of truth told softly.